Why urging our children to embrace different cultures and learn different languages matters

4. Why urging our children to embrace different cultures and learn different languages matters by Dr. Ute Limacher-Riebold

Click here for the index and access all the chapters.

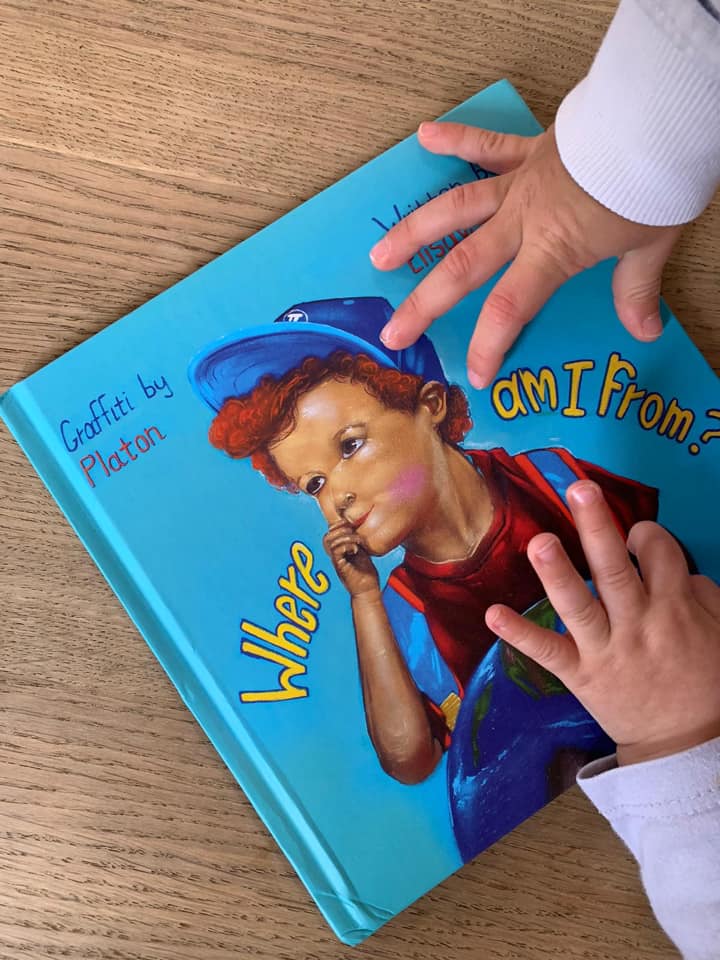

Like many others who were born in one country, brought up in another (or more), and then moved to other places, I used to struggle when people asked me where I am from or where my home is. As a child, I wondered why people would ask me which country I like most, Germany or Italy, or which language I prefer, German or Italian. I learned to give the answer that was expected from me and that made others happy: my parents, my family, and my friends. What I only discovered much later in life was that I wasn’t the only person having a hard time dealing with these questions. Children who grow up outside of their countries of origin, or out of their parents’ passport countries, actually have a name; Third Culture Kids (or Cross-Cultural Kids, etc.).

All of these children face more or less the same challenges. According to the latest definition of TCKs from Michael Pollock (3rd edition of “Third Culture Kids: Growing up among worlds”, 2017), “A traditional third culture kid (TCK) is a person who spends a significant part of his or her first eighteen developmental years of life accompanying parent(s) into a country (or countries) different from at least one parent‘s passport country(ies) due to a parent‘s choice of work or advanced training”.

I was born in Switzerland while my German parents were living just across the Italian border. I grew up in Lombardy (Italy) and moved to Switzerland for studies when I was 18. My parents left Germany in 1957 and after living in Belgium, moved to Italy for my father’s work for a European organization. My sister and I didn’t have a highly mobile childhood, but a childhood spent in different cultures: our parents’(German), the local (Italian), and the highly international one that we had the chance to immerse into at school, and in the community, we grew up in: our “third” culture.

I grew up knowing that as “guests in the country” (how our mother would explain our status as foreigners) we’d better adjust to the host culture in order to fully embrace our life there. My mother was a perfect example of how to do this: she taught herself Italian and was one of the few foreign spouses who preferred the connection with locals to the expat bubble. She would always see the positive side of everything. There were only a few situations that made me realize that the way we were living was not that common.

I never understood why others would call us “Germans” or foreigners in Italy and “Italians” or, again, foreigners in Germany. This being “neither… nor…” wasn’t a problem for me. I understood very early that only people who were not in our situation would ask these questions out of curiosity and because they wanted to know how a child perceived this kind of life.

For me, speaking German at home and Italian with my friends was normal, and although many of my local friends spoke the local language only, I never really thought that speaking three languages at age 6 was “strange”. Even though I saw that they would meet with their extended family regularly on the weekends and for special occasions, I never missed my extended family. I guess that if you don’t know something you don’t miss it.

It was only later when I was a teenager that I started comparing my life to the ones of my peers in Germany and Italy. I wondered how life would have been if my grandmother would have cooked for me as she did for my cousins, and what my birthdays would have been if my extended family would have been present. But again, it wasn’t a sad thought, it was one of curiosity. I didn’t long for a life more like theirs, I was simply curious to know what my life would have been should my parents have stayed in Germany.

It was at age 14, when I spent a few weeks with my aunts and grandparents alone in Germany, that I discovered my “Germanness”. I got a feeling of what life in Germany could be like. I spent a lot of time with my cousins who happened to be my peers. I did my best to fit in, to belong to the groups I was hanging out with. I listened to their music, used the same language and slang, and started understanding their jokes. For the first time in my life, I felt what it would be like living in a place where everyone speaks my home language. But I also felt sad because I had to hide my Italian self as nobody spoke Italian or knew about Italian culture.

Growing up as a German in Italy in the 70s/80s was not always a pleasure. When I was 8 a young child was forbidden to play with me because I was German – his grandfather died in WWII and the family resented all Germans for this loss. When Italy played against Germany at the FIFA world cup, my father hid our car with the German number plate in the garage, out of fear that someone would damage it. As a teenager, I avoided telling new friends that I’m German in order to fit in. I didn’t want to attract attention or be compared to the German tourists that would come to our town.

The desire to fit in and feel a sense of belonging in a group of friends is very natural and healthy. It means that we want to fully embrace the otherness. In the same way, I switched from one language to another, I switched my behavior and the way I presented myself from German to Italian, to my original Italo-German. It was my way to adapt with innate flexibility to different situations and settings. This kind of switching is very common among adaptable people, and it seems to be one of the many advantages of children who grow up between different cultures.

When I was 18 years old, I moved to Switzerland to study at the University of Zurich and learned to find my way to a new culture without my parents. I learned the importance of punctuality and that one can have dinner at 6 pm, among other things.

Although I enrolled in Romanistics, I studied several semesters of Germanistics, Psychology, English, and Journalism, just because I was fascinated by these topics. I obtained my University degree in Italian and French Literature and Linguistics, and did my Ph.D. in French Philology, I worked for 7 years as a lecturer, assistant, researcher, and editor at the University of Zurich. I then moved to Italy and worked on several projects in Italy. I obtained a 3-year research grant for advanced researchers and my husband and I moved to Italy, Florence. While I was doing research, my husband was taking care of our son who was born a year after our arrival in Italy.

When we moved to the Netherlands in 2005, my life shifted 180 degrees: I turned from sole breadwinner to accompanying partner (expat spouse) within 48 hours. – In the following years (!) I had a hard time accepting that I couldn’t pursue my former career if I wanted to take care of my son. At that time we didn’t have a network of trusted friends that would support us, so we could only rely on ourselves and an occasional babysitter to take care of by then three children. In the following years, I decided to learn new skills and assess those I already had, and I managed to find a new purpose: helping international families thrive during their life in another country. My volunteer work with expats helped me understand what they needed to lead a gratifying life. I became a Language Consultant and Intercultural Communication Trainer who helps internationals to understand their new culture and language while maintaining their home language.

I have experienced life in Switzerland, France, Italy, and the Netherlands, first as a child of expatriates, then as a student, as a researcher and sole breadwinner, and as an accompanying partner; as single, with a partner, with a child.

With every move and change of “home” was the opportunity to experience life in a new place, but one which came with the challenge of learning to assert myself in a new culture. People we meet in new cultural settings don’t know who we are or what we are capable of, and it takes time to gain their trust and prove that we are trustworthy.

We can accelerate this process by being proactive, connecting with locals, and building our new village that not only will be there for us if we need it but also for our children so that they can grow up in a community that will be their Ersatz family. Learning the local language and the rules, values, and beliefs of the host culture need to come naturally. My mother used to tell us that as we are guests in the country, we need to adapt and integrate. It starts with learning the language, learning the rules of the society we live in, and respecting the “otherness”. If we can adopt what we like and what feels aligned with our convictions and beliefs, and understand and respect what is different, we can thrive in every place.

I managed to adapt and thrive in all the places I lived so far, by being proactive, learning the language, and being curious and open-minded.

So far I have never lived in my parent’s passport country and as a real expat (living out of the parents’ passport country)-since-birth, I embrace this kind of life to the fullest and help others to do the same.

If you would like to have further information about how to lead a balanced and healthy life abroad, you can join the Families In Global Transition (FIGT = www.figt.org) on Facebook or follow me on my website.

NEXT CHAPTER: The 5 most common challenges a parent faces while raising a multicultural kid and how to address them

Click here for the index and access all the chapters.

Category: Uncategorized